A full-bore collision mid-Channel left a Class 40 smashed in half and its two skippers clinging to wreckage. Helen Fretter gets the full story

Thirty-one Class 40s started the CIC Normandy Channel Race on Sunday, 25 May, one of the first big races of the season. It had been a tough test from the outset, with 25 knots and a building forecast. By Tuesday there had been several retirements, including a collision between two boats on the start, a dismasting and gear failures. But the Class 40 is one of the most competitive fleets around – entries included Vendée Globe legends Michel Desjoyeaux and Vincent Riou, such is the level of experience.

The double-handed pairings had rounded the Isle of Wight, and were zigzagging their way across the English Channel and its tough tidal races. Jay Thompson, an American who has spent much of the last decade in France working with big IMOCA teams, was racing #Empowher with Irish co-skipper Pamela Lee. He recalls: “It was quite a hard race. We’d had 25-35 knots of upwind, basically the entire race. So everyone was really tired.”

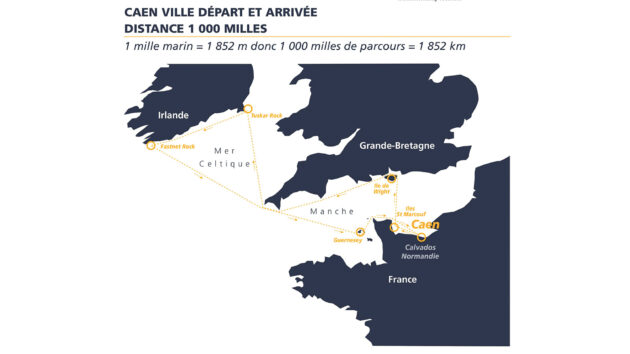

Faced with forecasts of 40+ knots in the Celtic Sea, race organisers had altered course to take the fleet back across the Ouessant Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS, or DST in French). This is common – the Class 40s, along with the Figaro and other classes, frequently race across the shipping areas, though the diversion meant this particular race would cross a TSS six times.

“We had just passed the most southern mark,” Thompson continues. “We were going upwind, but slightly open. It was like a tight reach, about 80° or so true wind angle. At that time, there was 25 knots, pretty steady, with 28 knot gusts sometimes. So mostly everybody was sailing with a J1 and one reef in the main. We were on port tack, sailing north – basically to Fastnet, which was going to be our last mark before we came back to Caen, to finish.

“There was pretty good visibility. And there were big waves, about 2.5m or so of swell because a large front had just passed through.”

Event map showing the original CIC Normandy Channel Race course

Busy traffic

Cédric de Kervenoaël and Thomas Jourdren were about a mile ahead of #Empowher on their sistership Pogo S4 NST Cabinet Z. Not all the Class 40 skippers are pro sailors – de Kervenoaël is a lawyer during the week, but has been offshore racing for 30 years, and in the Class 40 fleet for a decade. He is also class president. Co-skipper Jourdren, 25, is a préparateur for Class 40s and has competed in the Transat Jacques Vabre.

De Kervenoaël says: “It had been two days of really, really tough sailing because the boats are very hard now. The scows are not so difficult to sail, but difficult to live in. You cannot eat, you cannot sleep.

“We crossed the Channel very, very quickly. And when we rounded the buoy, near Ouessant, it was about 1800-1900. We were preparing for about 15 hours of very [high] speed [sailing] and the wind to be stronger when we arrived at the Fastnet.”

“I was not really sleeping inside, but I’d kept my oilskins on. Really I was wondering if I could put my oilskins out because everything was so wet, but I had no motivation to do that. That proved quite useful later.”

Thompson had a clear visual of NST Cabinet Z as they chased north. “We were slightly south and east of their position, just a bit to leeward. So I could see him quite well – well, I could see his navigation light as it was 0200 in the morning. We were on port tack, and so off to the port side is really clear. It’s really hard to see things that are on starboard because they’re underneath the sails and the waves and the spray.

Article continues below…

Coolest yachts: Class 40 Lift 2

The highly competitive Class 40 fleet has long been a proving ground for talent, both for designers and sailors, with…

Transat Jacques Vabre: lessons from the experts

Two boats achieved stunning victories in the latest edition of the Transat Jacques Vabre, establishing leads before the halfway mark…

“We were crossing the DST off Ouessant, which is the turning point. And it’s quite a busy one. My skipper, Pamela, was relaxing inside, and I was out in the cockpit just racing the boat. We have a screen on the outside, so I’m able to see the AIS and also do the sail adjustments at the same time.

“I noticed two cargos that were coming westbound. They would have been east of us. So they’re in that zone that’s difficult to see. And I could see that the crossing was going to be quite close. At that point, you’re paying more attention, and I’m trying to understand how I’m going to go around these two ships as well. Both boats had about 16-18 knots of boat speed or so.”

On board NST Cabinet Z Cédric de Kervenoaël heard his co-skipper on the VHF radio. “He was calling the cargo, but he was speaking very low, so I didn’t hear exactly what he said. But I learned afterwards that 25 minutes before the collision, he tried to call the cargo. The cargo didn’t answer. And after that, they answered.

“[Thomas] told them that, on the AIS, we were crossing in front of the cargo and he wanted to be sure that the cargo had seen us. And the guy answered, ‘Okay, I move my course’.”

“And maybe five or seven minutes after, I heard the same guy saying, ‘Well, you’re not a sailing boat, you take me for a piece of shit.’”

31 Class 40s started the 2025 CIC Normandy Channel Race, an approximately 1,000-mile double-handed offshore race around the English Channel and Celtic Sea. Photo: Photos: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

Not clear

Monitoring the situation, Thompson recalls. “I heard 191 (NST Cabinet Z) call one of the cargo ships and ask if he can pass ahead. And the guy responds by saying, ‘Yeah, you can pass ahead.’

“I would say by then we’re quite close to the cargo, getting within a mile or so – I did a couple of degrees [adjustment] to just pass behind it, and he was going to try to pass in front of it, basically in between the two cargos, because one was going to be clear ahead.

“Then a few moments later, the guy [on the cargo] comes back on the radio and says, ‘You are the give-way vessel. YOU are the one that’s going to move out of the way.’ And he says it in a way that’s really kind of unprofessional. It was more in his intonation – angry or upset.” Thompson didn’t hear anything further in the VHF exchange.

On NST Cabinet Z de Kervenoaël got up in alarm.

Cédric de Kervenoaël (on left) and Thomas Jourdren. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

“I said to Thomas, ‘Did you understand what he said?’ He was not sure, but I understood very well. So I took the radio, and I told them, ‘Yes, we are a sailing racing boat. That’s why we are fast.’ Because I suppose those guys are used to crossing sailing boats at 6.5 knots – not when they’re going at 15 knots.

“But the guy [on the cargo] didn’t answer me. I looked at the chart and I asked Thomas, ‘Okay, look, look, where is the boat? Where is the boat?’ He went outside and said, ‘It doesn’t cross, it doesn’t cross, it doesn’t cross!’

“And then we were crushed by the ship.”

Hit and run

Thompson had heard the conversation and noted it as odd. Watching from #Empowher. “I could see the Class 40 and the cargo ship’s lights coming together. And then I see just the cargo lights, so I assume he passed in front.

“Then I hear on the VHF a guy comes back on – which I assume is the cargo ship because he says, ‘You need to call the Cross.’ I thought that’s a weird thing to say.

“I waited maybe 30 seconds, the cargo ship continues on, and I don’t see the lights of the Class 40 anymore. Then I look at my screen, and their AIS has disappeared on the screen. I pick up the VHF and I call NST. She doesn’t answer. And so I tell Pam, there might be a situation here. Then a radio call comes in. He says, ‘Mayday, the boat is cut in half. We’ve de-masted. Come and get us now.’

Cédric de Kervenoaël and Thomas Jourdren were racing NST Cabinet Z. Photo: Photos: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

“It was very crackly because it was just a handheld VHF. So I responded, ‘Okay, we’re going to come right away.’”

Thompson readied his Class 40 – furling the jib and starting the engine, while Lee relayed the Mayday to the Cross Corsen – the French maritime rescue service. Jourdren had also activated the EPIRB on NST.

It’s not totally clear what the cargo skipper meant when he said ‘You need to call the Cross,’ but Thompson believes he was telling the yacht they needed to call the rescue services themselves after the impact. The ship did not stop to offer assistance.

“When I saw the AIS disappear, I just put a very quick waypoint on the Adrena of where it happened,” recalls Thompson, “So we headed over to that zone. We were there within 10 minutes.

“We could see that the boat was in pieces. The bow was apart but attached, and the mast laying in the middle with the sail. The cockpit was slightly sticking out of the water, but most of the back half of the boat was underwater.”

Class 40 rules require each yacht to have large blocks of foam for flotation built-in both forward and aft. “With the keel, the aft section was barely floating, nearly vertical. The crew were on the starboard pushpit. It was the only section that was out of the water, but with the waves, it was still going in the water. We could just see their reflectives on their jackets because we had a big spotlight. That’s how we spotted them,” Thompson adds.

The Cross rescue confirmed that a helicopter could be with them in 40 minutes. They also halted all shipping traffic in the area around the disabled yacht.

“We asked Cédric and Thomas: ‘Do you have your TPS survival suits?’ They said, no, all they had was a handheld VHF. So we relayed that, and the Cross said, ‘Well, you really need to try to get them off because 40 minutes in the water is going to be a long time.’

Pamela Lee and Jay Thompson are campaigning the Pogo S4 #Empowher. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

“We instructed the crew to inflate their liferaft, get into the raft, then let it float behind the boat. Because with the wreckage and everything in the big swell, it would have been almost guaranteed that we would put a hole in our boat if we even got close. But when they tried to inflate the liferaft, the liferaft didn’t open.”

Next the crew of #Empowher tried a different plan – inflating their own raft, with the intention of letting it drift down to the stranded crew. “We went just upwind of the boat and opened the raft. This was when it got really crazy because I looked down for two seconds to help Pam get the liferaft out of the back. And when we looked up we couldn’t see the boat anywhere. It happens so quickly that you can lose somebody. It took a little moment for us to search around to find them again.

“Then Pam opened the liferaft, and everything went perfect. She was holding on to the rope at the back of the transom. I’m driving the boat, trying to hold station, just to windward so that she could let the raft down to them. And then Pam tells me “There’s nothing on the rope.”

The rope had detached from #Empowher’s liferaft. Having had the scare of losing sight of the Class 40, Jay and Pam decided not to attempt to recover the raft, but instead to keep eyes on the crew – not an easy task short-handed.

“The boats are not easy at all. In one moment, you’re going super fast because you’re going downwind and down swell, kind of surfing. Then the next, you’re trying to go upwind super slow. And you’re trying to stay close, but not too close.

Pamela Lee and Jay Thompson on #Empowher. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

Pam was handling all the communications, I was just driving and trying to always keep a visual on the boat, basically making anticlockwise loops around them, which was easiest for me because the port side is where the controls are for the motor.”

Cedric and Thomas confirmed that their situation on the disabled NST Cabinet Z was stable – not sinking, but cold, so #Empowher kept circling for another 20 minutes.

“I think the most stressful part for us was when there was about 10 minutes left to go for the helicopter to arrive,” recalls Thompson. “Every time we did a circle, we would check in with them. But after that 10-minute point, we could start to hear in their voices how they were in themselves [going downhill] a bit. They were asking, ‘Where are you? Where are you guys? I don’t see you anymore.’”

Fortunately the helicopter arrived from Brest shortly after, and the rescue divers swiftly lifted the two men to safety – Jourdren first, as he was suffering from severe cold, then de Kervenoaël, who had broken four ribs in the impact, but – remarkably – both were otherwise unharmed.

Lessons learned

Both Thompson and de Kervenoaël commented on how the Offshore Personal Survival training had helped in the moment. “It was a bit terrifying,” admits de Kervenoaël.

“But as soon as we crashed and saw that we were both still on the boat, we did the job we had to do. The sea survival training was very useful. When you are in this situation, you know exactly what you have to do. So there was no panic. We knew that someone would come and that it would be too stupid to die in that place! It was just a question of time.”

However, Thompson notes that one thing that could improve the training is more on boat-to-boat rescues.

In a separate incident two Class 40s collided at the race start. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

“Actually there’s quite a lot of scenarios where one boat is assisting another sailing boat, and that’s often not really taught too much. It’s mainly about what happens when the helicopter comes or a cargo ship.

“For example, something I’d never actually thought about before, was that the rafts have something like 300kg of water ballast. So you can’t just drag it wherever. You either have to get rid of the water ballast once you deploy the raft, or make sure that you don’t inflate it until you’re in the exact right area.”

That two rafts failed in an emergency situation is something the class is taking very seriously. Both boats were carrying Waypoint rafts, favoured by Class 40 skippers for their light weight. The class has since mandated an alternative Plastimo raft, which is around 12kg heavier. Waypoint is also investigating the cause of the failures – Thompson confirmed he was visited by the manufacturer to discuss what happened and view the liferaft on NST Cabinet Z (the Class 40 hull was salvaged).

Cédric de Kervenoaël speaks to the media after his dramatic rescue. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

De Kervenoaël says the class will also look into liferaft positioning (both the Pogo S4s had their raft stowed on the transom), and how grab bags can be best secured within reach. “Maybe it should be attached somewhere because I was very lucky to find it floating beside the boat. But if we hadn’t had the grab bag, with the VHF, it would have been another story.”

The collision itself is subject to a police investigation. The cargo ship Ital Bonny, which was Italian flagged, was intercepted by a French warship and escorted to shore.

“Clearly, a conversation was going on about taking avoiding action, and for some reason, that didn’t happen. In terms of the angle [crossing the TSS], there was no fault. The race crew did everything right,” an experienced Class 40 sailor told me, who didn’t want to be identified.

However, as the confusion on the VHF shows, calling a cargo ship is no guarantee of a safe outcome. “I basically never call the ships,” says Thompson, “just because in my experience, it’s very rare that it goes well. Often you have a lot of different nationalities so it’s quite difficult to speak with them. So I think that should be your secondary step – if you need to do it. The very first step should be to adjust your course early so that it doesn’t become an issue.

Cédric thanks Thompson and Lee for their part in saving him and his co-skipper. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot/CIC NCR

“When we’re crossing the lanes, closing speed starts to get so quick because we’re averaging between 16-18 knots, and the cargos are going anywhere from 12-18 normally. When you’re going 6 knots, you have so much more time.

“So it’s really important to get that visual – because the moment you get a visual, normally you can tell fairly easily how it’s going to cross. Sometimes it’s difficult, and you have to do that painful thing of letting the sheets go and the boat slow down a bit, or even turn downwind for a second to make sure that you can really see.

“Often, those decisions that we figure would be quite standard end up being really difficult when you haven’t slept for a couple of days. It’s definitely the most stressful and difficult thing on these races, because we’re basically crossing a freeway on a bicycle.”

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

The post ‘Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! The boat is cut in half’ appeared first on Yachting World.