Gitana 18 is the newest foiling Ultim trimaran is a melting pot of crazy ideas that could potentially fly at 55 knots. Helen Fretter gets a look on board

Lorient is the Hollywood of ocean racing. Like the movie factory of Los Angeles, the Brittany port is a seemingly single-purpose town that draws dreamers. And just as Hollywood is La La Land, so Lorient attracts some of the most outlandish projects in sailing.

The La Ter river is dotted with small yachts bobbing on moorings, awaiting gentle adventures in the tiny creeks and sandy beaches of southern Morbihan. But the estuary’s north shore is different. This is home to the concrete wonderland of La Base, a former U-boat submarine base that is today’s epicentre of ocean racing. A walk around the pontoons here is a chance to window-shop the most extreme offshore technology.

Gitana’s team base is in prime position, a nearly 2,000m2 boat shed with Bond-lair-esque rolling walls to shutter its secrets. Since 2022 the work inside has been kept closed and confidential, but in early December the base was thrown open to unveil Gitana 18, the newest 100ft foiling trimaran.

The Y-foils cant on giant swinging arms

A passion for sailing

Gitana is the racing stable of the Rothschild family, a banking dynasty synonymous with generational wealth on an epic scale. Their passion for sailing has equally been handed down, and Gitana 18 marks 150 years of the family’s deep involvement in yachting, currently spearheaded by matriarch Ariane de Rothschild.

This history shapes the fundamental reason for building a new boat. Unlike most corporate sponsorships, Gitana 18 is not built to score column inches. She is not even entirely built to win. Gitana 17, the previous Ultim launched in 2017 and the first giant tri to take flight, has basically already won most things.

“What we’re doing here is really on another level, but it’s also going to be a risk,” explains project manager Sébastien Saison. “If we had wanted to be 100% sure that we’re going to win the next Route du Rhum in 2026 we would have gone safer. It would have just been a bit of an evolution. But we know that’s not the future.”

It was the opportunity to do something extraordinary that drove the project. “Otherwise we wouldn’t have had the chance to build a new boat.

The Y-foils also have two adjustable flaps

“Ariane de Rothschild was quite clear about it: if they invest, and if we are to do a new boat, it has to be disruptive. It has to be another level up,” recalls Saison.

“So it was part of the scope of work, to say ‘Okay, do a new boat, but show me you can do something really crazy.’ Obviously for a naval architect or an engineer, it’s always nice to hear! But we couldn’t have known at the beginning what we would have ended up with.”

So Gitana 18 isn’t just about collecting trophies. It’s about the creation of an epic. In pursuit of the two great achievements that eluded her predecessor – solo and crewed non-stop around the world records – it’s a boat built for experimentation on a grand scale. And that is why it looks quite so mad.

The 121ft mast can be bent underway using hydraulic rams around the spreaders

Full flight

The most obviously extraordinary things about Gitana 18 are the appendages. The goal of this boat is 100% air-time, flying across oceans at 40+ knots, and the resultant foils are phenomenal in both scale and shape.

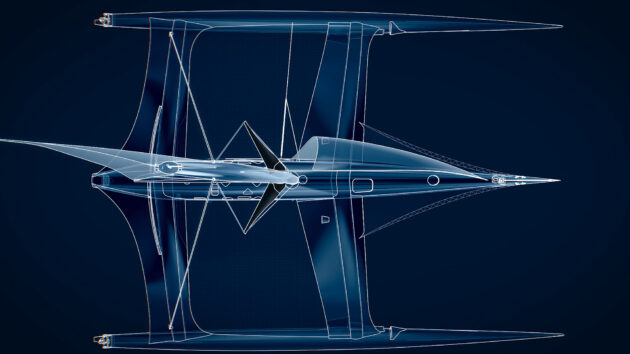

While the previous generation Ultims have L-foils that plunge through their outer hulls before curving inwards, Gitana 18 sports giant T- or Y-foils on swinging arms that lift up between the crossbeams. Beneath the central hull is a huge ‘skate wing’ T-board. And most baffling of all are the rudders, which are like no other rudders seen before. They have a ‘U’ or A-frame shape with twin chords and a horizontal base plate.

The foils, which the team refer to as Y-foils, show a clear lineage from those on the AC75s, though Gitana’s will lift inwards to meet the Ultim maximum beam rule. Their wings span more than 5m, the bulb 2m long.

One key target is to enable the boat to take off earlier. Skipper Charles Caudrelier explained that the old Gitana needed to be sailing at around 22-24 knots to accelerate and take flight. These new foils could reduce that to less than 20 knots of boatspeed, in potentially as little as 10 knots of windspeed.

At the upper end of the range, cavitation is another problem they’ve worked to address. “When I reached 37 knots on Gitana 17, all the appendages started to cavitate. So that means lots of drag, and also lots of damage on the foils. They degrade very quickly. It’s a nightmare,” Caudrelier explained.

The radical A-frame rudders are deeper, thinner, but theoretically more resistant to deformation

“We pushed the limit with a second generation of foils up to 40-42 knots. But in surfing conditions sometimes you can’t stop the boat. You have a big wave, plus a gust, and you go to 45, 47 knots – and then all the boat vibrates, and you know you’re damaging them. You know that at the end of the race, you’ll have lost 10%, 20%, even 30% of the performance of the boat because of degradation. It starts to impact the paint. Then it goes through to the carbon. In the end, you can break the foil because you’ve lost skin on skin. At the end of the race around the planet, I was sailing at 70% of my performance in perfect conditions because the foil was completely destroyed.

“That’s also why we like canting foils because another problem before was that my windward foil was up, but it was hitting the water and damaged a lot in the elbow. By canting them, we can pull it up off the water and they’ll have no contact.

“We expect these foils to degrade much less. Then at the end of the race, we’ll still be at 100% – if we don’t meet a rock or a piece of wood. That’s a game changer.”

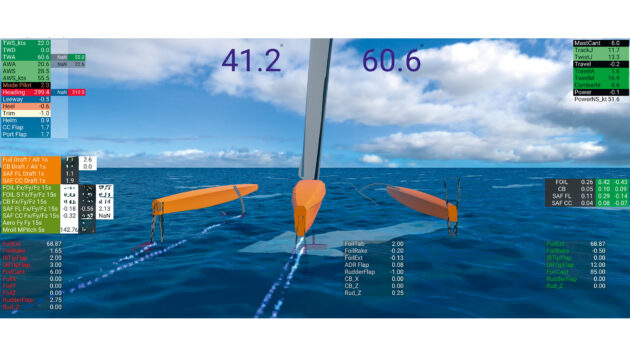

The in-house simulator was used to process vast amounts of data and help sailors visualise the boat’s behaviour

Minutely trimmed

The ‘skate wing’ T-board beneath the boat is now a massive, sculptural piece of metal (the team won’t disclose which one) which will be more resistant to this degradation. It is 30% bigger than the previous boat’s. The switch from carbon to metal is because, while metal is a little less efficient, it offers a better overall balance of stiffness against both torsion and bending.

The T-board version we were allowed to see (but not photograph) had a tattoo etched in the surface which will carry fibre optic sensors to measure how much this metal is contorting under the sea – just some of the 500 sensors Gitana 18 will carry (double the number on 17). Designer Guillaume Verdier described the boat as like a creature capable of telling its crew when it is in pain.

Cyril Dardashti, team manager; owner Ariane de Rothschild; and skipper Charles Caudrelier at Gitana 18’s grand unveiling. Photo: Marie Rouge/Gitana SA

The metal skate wing should also be more robust in case of collisions. The central bulb contains pinger technology to warn marine mammals of its approach.

The physics driving these foil shapes will require whoever is piloting to trim complex underwater interactions over multiple planes, often while sailing solo. This a very different prospect to a full-time flight controller minutely trimming the foils of an AC75 over a windward-leeward Cup course. The Y-foils alone can be canted, raked, and each wing has independently adjustable flaps on the trailing edges.

“You have to change the trim of the [foil] depending on sea state, because the sea state makes a big difference in speed,” explains Caudrelier. “So if the sea state is flat, the wing is horizontal. If the sea state is larger, we have to put it more vertical because it helps when the boat accelerates. The boat starts to fly higher because the foils lift more. Then part of the wing goes in the air, so the foils lift less.

“That is the game, which is very complicated.”

The grand unveiling. Photo: Marie Rouge/Gitana SA

The flexi-rig

Another tool at Caudrelier’s disposal will be the rig, shipped over from Southern Spars – the first the New Zealand builders have made for the Ultim class.

The 121ft spar is capable of impressive levels of flex. The problem, Caudrelier explains, is that when you are building speed and power to take off, particularly in lighter airs, you need camber in your rig. But when in flight mode you need it flattened off to depower.

The solution is a mast which can be bent, with the spreader angles flexing by up to 35° to create camber in the middle of the section. Rams control the power – one on each spreader – in a system which can be handled by a solo sailor, rather like cranking on the Cunningham on a dinghy or windsurfer rig.

Article continues below…

The ability to depower should also reduce the number of headsail changes or reefs required. “I can very quickly change the angle of the spreaders, then I can adapt my power to the wing and to the speed of the boat. That’s very, very fast,” notes Caudrelier.

Despite the intimidating forces involved, he says the rig is actually simple to handle. “But to do it on a canting wing mast, and such a big mast – that has never been done before. And how to manage it with only one guy on board? That took a lot of brain hours!”

Gitana 18 was moved under cover of darkness. Photo: Eloi Stichelbaut/polaRYSE/Gitana SA

Radical Rudders

Control is what led to the creation of the outlandish rudders, the most unique feature of Gitana 18. To improve steerage when flying at faster speeds, high above the waves, the team wanted to lengthen the rudders. The problem is that the huge loads they are subjected to, means they can deform, twist and shear, leading to sudden loss of control.

The new U-shaped rudders do not rotate – instead they have trailing edge flaps on each vertical chord, which provide steerage like an aeroplane wing. Each rudder also has a horizontal elevator, which in turn has an adjustable flap to control trim. This rigid structure enables the rudders to be much deeper – at over 4m they are a metre longer than on Gitana 17 – and resistant to cavitation. They are also thinner hence, somewhat counterintuitively given their shape, there is no drag penalty.

But they’ve never been made before. There has been no tank testing and no scale models built – just a lot of CFD and data analysis, and enormous trust in the process.

The problem, Saison explains, is that when you are designing something that has never been done, there is no data to work from. “When we started designing those rudders, the software for designing them didn’t exist. The simulator didn’t understand them and physically couldn’t calculate them. So in the same time as we’ve invented those rudders, we had to invent a new code for the simulator. We had to invent a new programme to calculate the structure. Obviously, those programmes are not as well proven as the one for the foils. So that brings another little level of stress.”

Caudrelier is confident. “On a car, you can have a super engine, but in Formula 1 today sometimes you lose a race because of your tyres. You can have the best car, but if your tyres are not good, you cannot be very accurate and you have to reduce your speed. It was exactly the same on Gitana 17. Sometimes we felt the rudders were overloaded. We knew that if we didn’t reduce the load, we were going to damage them, or it’s going to twist and we’d lose control. More control means you can push harder.”

The boat was precision built at CDK Technoloiges in Lorient, with up to 80% made in an autoclave. Photo: G Le Corre/polaRYSE/Gitana SA

Visualisation

Because this rudder shape had never been tried before, even the most high-tech autopilots weren’t suitable. So, in an ambitious side quest, Gitana developed its own. This also helped keep a project of such complexity top secret, in a town where everybody works in the same industry.

One key weapon was their in-house simulator. Derived from the Team New Zealand America’s Cup sim, Gitana has now developed an offshore foiling simulator tool like no other. Over three years Caudrelier says they ‘sailed’ for thousands of hours on it, initially verifying the vast data accumulated from eight years of optimising Gitana 17, and focussing on improving how the simulator handled variances of sea state.

Caudrelier explained: “Over the last three years, the improvement in the sim has been huge – because we’ve had no boat, we’ve spent hours and hours ‘sailing’ the simulator and developing it. Now it’s really accurate.

“Before it was just numbers and no sensation, no feeling. Now we can really test the foils, rudder, everything, and give our feedback to the designer. It’s completely changed the way we work.”

200,000 man hours have gone into Gitana 18’s construction. Photo: G Le Corre/polaRYSE/Gitana SA

The autopilot was subject to some eight months of daily testing. “It works like a helmsman,” Caudrelier enthuses. “It understands how the boat works, can adjust the height of the flight, can visualise the boat in 3D and anticipate its movements. In terms of performance, it’s amazing what we can achieve with it.” The major limitations will be what the class rules permit in terms of automation.

The cockpit of this 100ft goliath share some features with the latest IMOCAs, particularly Charlie Dalin’s Vendée winning Macif. Like Dalin, Caudrelier requested his living space be behind the working cockpit area. The cockpit is also fully enclosed. But once inside, what strikes you most are the irregular-shaped portholes punched through the roof and sidewalls. Gitana 18 is the first new trimaran built to meet the latest Ultim rule on visibility, and their positioning was created with Caudrelier to enable him to maintain a lookout, and view sail trim.

Sébastien Saison (left), Caudrelier (seated) and team discuss the finer details of construction mid-build. Photo: Eloi Stichelbaut/polaRYSE/Gitana SA

Anything goes

Gitana 18 was a year in conceptual development before build even began. The team adopted a ‘try anything’ approach, working with the most innovative and free-thinking designer of a generation in Guillaume Verdier. “The whole idea of the boat – and Guillaume loves working like that – is to say, don’t think about the problems now. Think about what would be the most crazy thing,” explains Saison. “The rudders are one example. If you say, ‘Oh, it’s going to be super complicated. How are we going to attach them to the boat?’ If you start thinking like that, you don’t do it.”

Verdier himself commented: “being so lucky to create such a work of art in a career is rare.”

While the project’s ambition was unlimited, that doesn’t mean the budget was, as Ariane de Rothschild explained: “When we work under tension and pressure is when we work better. So it’s very important to put in budget caps that are reasonable.”

Caudrelier (left) working in VR goggles to visualise the cockpit layout, sight lines etc.

But reasonable is relative. They will likely never disclose exactly how much this extraordinary project cost, but one team member did emphasise that their 30-person operation runs at quite a bit less than an America’s Cup campaign. Meanwhile the previous boat was listed for sale at €15million, so the answer likely lies somewhere in the very big space between €15million and €50million.

Far more important is what it can do. “The top speed, I think we’ll manage above 55 knots, which is a lot for a big boat. But that’s not what we’re looking for,” explains Saison. “What we’d like is to have average speeds above of 40 knots all the time.

“The around the world time is very hard to say because already on the previous boat, it was 35, 38 days. If you had perfect routing, I’m sure that the times would be just about 30 days now, but it’s never going to happen because of the weather. But if you can go at 40 knots average around the world, it would be 32 or 33 days.”

And that would be something truly extraordinary.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

The post The smartest boat ever built? 500 sensors, custom autopilots, and the future of foiling appeared first on Yachting World.